News & Insights

Latest news and legal insights from HANBYOL LAW LLC.

Back to List

Is this the kind of embarrassment or despondency that occurs when a target disappears? That's exactly how this reporter felt when Kim Yong-joon, a candidate for prime minister, "abruptly" withdrew from the race on the afternoon of Jan. 29th.

The reporter had learned that Kim Yong-joon was the presiding judge of the Supreme Court in the Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support case (the "Second Appeal" to be precise) and prepared several series of articles. The plan was to interview Kim Yong-won, a former prosecutor who investigated the Busan Brotherhood Welfare Center case (now the head of the law firm Han Byul), and Han Jong-sun, a victim who was taken to the center when he was 9 years old (in 1984) (co-author of "The Surviving Child").

First, I tried to contact Kim Yong-won, a former prosecutor I knew, but he said he was "out of the country." It was a lost cause. I agreed to meet with him upon his return to Korea and suspended the interview. Han Jong-sun, who lives in the province, arranged a meeting in Seoul on Jan. 30 through Moonju Publishing House, the publisher of <The Surviving Child>.

When the interview with former prosecutor Kim, who would have known the circumstances of the investigation better than anyone else, ran into difficulties, I remembered his 1993 book, <i>Benz Without Brakes. In the first chapter, the book details the Busan Brothers case. I decided to report the contents of the book first, and wrote an article and shipped it on January 29 at 1 pm.

But at 7 p.m. on the day I published the article, I received news that Kim Yong-joon had withdrawn. The Busan Brotherhood Welfare Center case, which had returned to the social agenda after 26 years, would be buried with Kim's resignation. The Democratic Unity Party planned to use the victim, Han Jong-sun, as a witness in Kim's confirmation hearing. But the plan had to be stopped. The DPP met with Kim at his lawyer's office in Gangnam on May 5 to discuss the situation.

"The Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support Case is the 'Busan version of the Crucible Case'?"

The Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support Incident shook the world in 1987, but it quickly faded from the public eye. Was it because the torture and murder of Park Jong-chul, the catalyst for the democratization movement, symbolized '87 so much? However, as Marx observed long ago, history returns "once as a comedy and once as a tragedy," and the Brothers' Boksuwon case came back to haunt us when Kim Yong-joon, the chairman of the presidential transition committee, was nominated as a candidate for prime minister. It was 26 years after the incident.

Some have dubbed the Busan Brotherhood case the "Busan version of the Crucible. "It's a serious case of human rights violations, but it's a comedy," Kim said.

"The fraternity house was a place where if you didn't listen to them, they would beat you to death. You could actually get beaten to death there. There is no point in sexual assault and molestation (in the Crucible case) when lives are coming and going like this."

"Prisoners were beaten to death," Kim wrote in his book, "A Benz Without Brakes," and "doctors would sign off on the medical certificates of the beaten prisoners as having died of natural causes, and their bodies would be sold to medical schools for training.

"Bokjiwon got the skin from a slaughterhouse in Busan. The skin was industrial waste, so he couldn't sell it. He added spinach and dried radish to it and boiled spinach soup. I fed it to her every day. He also contracted pulmonary tuberculosis, but they didn't treat him and put him in a dark dormitory. There was no heating and no sunlight. They wanted people with TB to die. That's what it was like."

"It wasn't 10 people, it wasn't 100 people, it was 3,000 people," Kim said, adding, "No civilized country would imprison 3,000 people in one place, but it was hard to call South Korea a civilized country at the time."

Prosecutor's command 'obstructs investigation,' court gives 'impunity' for incarceration

Kim's dogged investigation revealed the true nature of Busan Brotherhood Support, including illegal imprisonment and embezzlement of state subsidies. Based on this, the prosecution asked for 15 years in prison and a fine of more than 600 million won in the first trial. The sentence was reduced from the 20 years in prison and 1.1 billion won in fines that former prosecutor Kim had in mind. This was the result of an "order" from the prosecutor's command at the time. Their "obstruction" of the investigation had already crossed the line.

"A large team of investigators has been set up to look into the assault and molestation of women. After organizing an investigation team of 30 people with the support of police personnel, we picked up typewriters one by one and sent them to the welfare center. Then we went to the Busan District Prosecutor's Office for permission, but they refused. The command did not authorize the investigation because it would take a large number of people to confirm it. At the time, the Busan District Prosecutor was Park Hee-tae (former Speaker of the National Assembly), and the deputy prosecutor was Song Jong-joong (former head of the legal system)."

"The upper echelons of the prosecutors' office is an organization that obstructs investigations," Kim said, adding, "Even in the case of the suspected civilian inspections, didn't the chief of the prosecutors' office play a leading role in obstructing investigations?" He pointed out.

Nevertheless, the first trial court sentenced him to 10 years in prison and a fine of more than 600 million won. However, in the first appeal, the sentence was drastically reduced to 'four years in prison' without the fine, then 'three years in prison' in the second appeal, and 'two years and six months in prison' in the third appeal. The three appeals were held because there were two appeals (Supreme Court).

In the first appeal hearing held in March 1988, the Supreme Court ruled that "the dormitory facility at the Ulju workshop in question was not illegal as it was set up to guide and protect vagrants and prevent them from escaping at night," and that "this constituted a legitimate performance of duty apart from social condemnation." The court did not recognize the crime of 'illegal confinement,' which even the appeals court had recognized, and sent the case back to the Daegu High Court. Kim Yong-joon was not involved in the first appeal.

The Daegu High Court ruled that "the dormitory facilities of the Ulju Workshop were originally located elsewhere, but were illegally transferred to the current location, so the crime of confinement can be applied." It repeatedly recognized the crime of 'illegal confinement'. However, at the second appeal hearing in November 1988, the Supreme Court did not recognize the crime of illegal confinement. "It was a legitimate act of duty to house the vagrants in the Ulju workshop for protection purposes, and locking the door at night to prevent them from escaping at night did not constitute criminal confinement," the court ruled. The presiding judge at the time was candidate Kim Yong-joon.

The Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support Case, which nakedly exposed the barbaric fifth-gong regime, came to a shameful end before the weak judiciary.

"Incarceration to protect? That's depriving the body of its liberty."

26 years after the incident, Kim is still furious with the Supreme Court for not upholding his confinement on two occasions (the first and second appeals). "I don't trust the Supreme Court justices," he said, criticizing them for "talking about human rights in their sleep."

"The iron gates of the fraternity house were announced. The gate itself was ironclad. They locked us inside, they locked us outside, and they beat us like dogs and killed us. How is this not a crime of imprisonment? The court was the handmaiden of the regime."

"There are only two cases in which a person can be held against his or her will: by an arrest warrant or to treat a schizophrenic patient," Kim said, adding, "But the inmates of the Brothers' Home were held against their will, and I don't understand why this does not constitute confinement."

"In the old days, we used to use the term 'protection' a lot. We used to put prostitutes and vagrants in jails or institutions to 'protect' them. But that's not protection. It's depriving them of their physical freedom. This is only possible in totalitarian countries. The more backward countries imprison people in the name of 'protection'. They justify it as 'protection' when it's clearly illegal."

In this respect, the Supreme Court's decision in Busan Brotherhood Support was "a legal recognition of unlawful detention as a protection." The court did not recognize the crime of confinement even though it was a serious matter of violating physical freedom through confinement. "The core crimes in the Brotherhood Welfare Case are confinement and embezzlement of state subsidies," Kim criticized, "but the most important crime is confinement, and our court says it is legal." He reiterated that "the ruling in the Brotherhood Welfare Case is a ruling that has lost its social legitimacy."

"If the Supreme Court had disagreed with the first appeal during the second appeal (when Kim Yong-joon was president), it could have referred it to the en banc. But it didn't. It did not correct the first appeal. It did not correct the first appeal, which means that the second appeal panel fully sympathized with and agreed with the outcome of the first appeal."

Interestingly, the lawyer who defended Park was a former Supreme Court justice. Former Supreme Court Justice Jeon Sang-seok (who passed away in 2001) had just started practicing law (1986) when he took on Park's defense.

"The original fine imposed by the prosecution and the first trial court was 680 million won, but it was reduced to 100 million won. So how much did the lawyers receive (in fees, etc.) for getting him acquitted of the crime of confinement?"

"An event that sparked interest in what bodily liberty is."

The crucial period of the democratization movement, '87, began with the Park Jong-chul torture and murder case and the Busan Brotherhood support case. While the former became an important catalyst for the democratization movement, the latter still has not received sufficient historical evaluation. "The historical evaluation of the Busan Brotherhood Support Case is insufficient," Kim said.

"But it was an event that was inevitably going to happen in the process of democratization. Chun Doo-hwan's regime locked up beggars because they wanted to show off that they had a very good welfare system and didn't have any beggars on the streets. However, this case exposed the barbaric regime's nakedness, and the level of our society along with the judiciary's nakedness. It was a case that stimulated the interest of our society, especially in relation to what physical freedom is."

In closing, Kim expressed special thanks to then Ulsan District Chief Cho Jae-seok. "If he hadn't pushed me to investigate, I wouldn't have been able to do it," he said.

"With that support, we've released 3,000 people. Our biggest accomplishment is not getting convictions. If you're convicted, what do you do? You do two and a half years and then you get out.... Our biggest accomplishment was freeing 3,000 people."

뉴스2013년 5월 12일

"I don't trust Supreme Court justices... The court is the handmaiden of the regime."

| [取中眞談] is a column where <Oh My News> full-time reporters write about their experiences, stories, and episodes in a free-flowing manner. [편집자말] |

| |

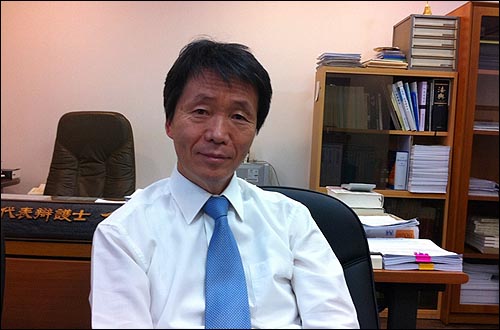

| ▲ Former prosecutor Kim Yong-won, who investigated the 1987 Busan Brotherhood support case. | |

| ⓒ 구영식 | |

Is this the kind of embarrassment or despondency that occurs when a target disappears? That's exactly how this reporter felt when Kim Yong-joon, a candidate for prime minister, "abruptly" withdrew from the race on the afternoon of Jan. 29th.

The reporter had learned that Kim Yong-joon was the presiding judge of the Supreme Court in the Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support case (the "Second Appeal" to be precise) and prepared several series of articles. The plan was to interview Kim Yong-won, a former prosecutor who investigated the Busan Brotherhood Welfare Center case (now the head of the law firm Han Byul), and Han Jong-sun, a victim who was taken to the center when he was 9 years old (in 1984) (co-author of "The Surviving Child").

First, I tried to contact Kim Yong-won, a former prosecutor I knew, but he said he was "out of the country." It was a lost cause. I agreed to meet with him upon his return to Korea and suspended the interview. Han Jong-sun, who lives in the province, arranged a meeting in Seoul on Jan. 30 through Moonju Publishing House, the publisher of <The Surviving Child>.

When the interview with former prosecutor Kim, who would have known the circumstances of the investigation better than anyone else, ran into difficulties, I remembered his 1993 book, <i>Benz Without Brakes. In the first chapter, the book details the Busan Brothers case. I decided to report the contents of the book first, and wrote an article and shipped it on January 29 at 1 pm.

But at 7 p.m. on the day I published the article, I received news that Kim Yong-joon had withdrawn. The Busan Brotherhood Welfare Center case, which had returned to the social agenda after 26 years, would be buried with Kim's resignation. The Democratic Unity Party planned to use the victim, Han Jong-sun, as a witness in Kim's confirmation hearing. But the plan had to be stopped. The DPP met with Kim at his lawyer's office in Gangnam on May 5 to discuss the situation.

| |

| ▲ Kim Yong-won, a former prosecutor, criticized the Supreme Court for "judging Won's actions as lawful under a flawed premise." | |

| ⓒ 오마이뉴스 | |

"The Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support Case is the 'Busan version of the Crucible Case'?"

The Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support Incident shook the world in 1987, but it quickly faded from the public eye. Was it because the torture and murder of Park Jong-chul, the catalyst for the democratization movement, symbolized '87 so much? However, as Marx observed long ago, history returns "once as a comedy and once as a tragedy," and the Brothers' Boksuwon case came back to haunt us when Kim Yong-joon, the chairman of the presidential transition committee, was nominated as a candidate for prime minister. It was 26 years after the incident.

Some have dubbed the Busan Brotherhood case the "Busan version of the Crucible. "It's a serious case of human rights violations, but it's a comedy," Kim said.

"The fraternity house was a place where if you didn't listen to them, they would beat you to death. You could actually get beaten to death there. There is no point in sexual assault and molestation (in the Crucible case) when lives are coming and going like this."

"Prisoners were beaten to death," Kim wrote in his book, "A Benz Without Brakes," and "doctors would sign off on the medical certificates of the beaten prisoners as having died of natural causes, and their bodies would be sold to medical schools for training.

"Bokjiwon got the skin from a slaughterhouse in Busan. The skin was industrial waste, so he couldn't sell it. He added spinach and dried radish to it and boiled spinach soup. I fed it to her every day. He also contracted pulmonary tuberculosis, but they didn't treat him and put him in a dark dormitory. There was no heating and no sunlight. They wanted people with TB to die. That's what it was like."

"It wasn't 10 people, it wasn't 100 people, it was 3,000 people," Kim said, adding, "No civilized country would imprison 3,000 people in one place, but it was hard to call South Korea a civilized country at the time."

| |

| ▲ Paintings drawn by Han Jong-sun, a victim of the Busan Brotherhood Support Incident. | |

| ⓒ 문주출판사 제공 | |

Prosecutor's command 'obstructs investigation,' court gives 'impunity' for incarceration

Kim's dogged investigation revealed the true nature of Busan Brotherhood Support, including illegal imprisonment and embezzlement of state subsidies. Based on this, the prosecution asked for 15 years in prison and a fine of more than 600 million won in the first trial. The sentence was reduced from the 20 years in prison and 1.1 billion won in fines that former prosecutor Kim had in mind. This was the result of an "order" from the prosecutor's command at the time. Their "obstruction" of the investigation had already crossed the line.

"A large team of investigators has been set up to look into the assault and molestation of women. After organizing an investigation team of 30 people with the support of police personnel, we picked up typewriters one by one and sent them to the welfare center. Then we went to the Busan District Prosecutor's Office for permission, but they refused. The command did not authorize the investigation because it would take a large number of people to confirm it. At the time, the Busan District Prosecutor was Park Hee-tae (former Speaker of the National Assembly), and the deputy prosecutor was Song Jong-joong (former head of the legal system)."

"The upper echelons of the prosecutors' office is an organization that obstructs investigations," Kim said, adding, "Even in the case of the suspected civilian inspections, didn't the chief of the prosecutors' office play a leading role in obstructing investigations?" He pointed out.

Nevertheless, the first trial court sentenced him to 10 years in prison and a fine of more than 600 million won. However, in the first appeal, the sentence was drastically reduced to 'four years in prison' without the fine, then 'three years in prison' in the second appeal, and 'two years and six months in prison' in the third appeal. The three appeals were held because there were two appeals (Supreme Court).

In the first appeal hearing held in March 1988, the Supreme Court ruled that "the dormitory facility at the Ulju workshop in question was not illegal as it was set up to guide and protect vagrants and prevent them from escaping at night," and that "this constituted a legitimate performance of duty apart from social condemnation." The court did not recognize the crime of 'illegal confinement,' which even the appeals court had recognized, and sent the case back to the Daegu High Court. Kim Yong-joon was not involved in the first appeal.

The Daegu High Court ruled that "the dormitory facilities of the Ulju Workshop were originally located elsewhere, but were illegally transferred to the current location, so the crime of confinement can be applied." It repeatedly recognized the crime of 'illegal confinement'. However, at the second appeal hearing in November 1988, the Supreme Court did not recognize the crime of illegal confinement. "It was a legitimate act of duty to house the vagrants in the Ulju workshop for protection purposes, and locking the door at night to prevent them from escaping at night did not constitute criminal confinement," the court ruled. The presiding judge at the time was candidate Kim Yong-joon.

The Busan Brotherhood Clothing Support Case, which nakedly exposed the barbaric fifth-gong regime, came to a shameful end before the weak judiciary.

"Incarceration to protect? That's depriving the body of its liberty."

26 years after the incident, Kim is still furious with the Supreme Court for not upholding his confinement on two occasions (the first and second appeals). "I don't trust the Supreme Court justices," he said, criticizing them for "talking about human rights in their sleep."

"The iron gates of the fraternity house were announced. The gate itself was ironclad. They locked us inside, they locked us outside, and they beat us like dogs and killed us. How is this not a crime of imprisonment? The court was the handmaiden of the regime."

"There are only two cases in which a person can be held against his or her will: by an arrest warrant or to treat a schizophrenic patient," Kim said, adding, "But the inmates of the Brothers' Home were held against their will, and I don't understand why this does not constitute confinement."

"In the old days, we used to use the term 'protection' a lot. We used to put prostitutes and vagrants in jails or institutions to 'protect' them. But that's not protection. It's depriving them of their physical freedom. This is only possible in totalitarian countries. The more backward countries imprison people in the name of 'protection'. They justify it as 'protection' when it's clearly illegal."

In this respect, the Supreme Court's decision in Busan Brotherhood Support was "a legal recognition of unlawful detention as a protection." The court did not recognize the crime of confinement even though it was a serious matter of violating physical freedom through confinement. "The core crimes in the Brotherhood Welfare Case are confinement and embezzlement of state subsidies," Kim criticized, "but the most important crime is confinement, and our court says it is legal." He reiterated that "the ruling in the Brotherhood Welfare Case is a ruling that has lost its social legitimacy."

"If the Supreme Court had disagreed with the first appeal during the second appeal (when Kim Yong-joon was president), it could have referred it to the en banc. But it didn't. It did not correct the first appeal. It did not correct the first appeal, which means that the second appeal panel fully sympathized with and agreed with the outcome of the first appeal."

Interestingly, the lawyer who defended Park was a former Supreme Court justice. Former Supreme Court Justice Jeon Sang-seok (who passed away in 2001) had just started practicing law (1986) when he took on Park's defense.

"The original fine imposed by the prosecution and the first trial court was 680 million won, but it was reduced to 100 million won. So how much did the lawyers receive (in fees, etc.) for getting him acquitted of the crime of confinement?"

| |

| ▲ The verdict of the second appeals court, where former prime ministerial candidate Kim Yong-joon was the presiding judge. | |

| ⓒ 오마이뉴스 | |

"An event that sparked interest in what bodily liberty is."

The crucial period of the democratization movement, '87, began with the Park Jong-chul torture and murder case and the Busan Brotherhood support case. While the former became an important catalyst for the democratization movement, the latter still has not received sufficient historical evaluation. "The historical evaluation of the Busan Brotherhood Support Case is insufficient," Kim said.

"But it was an event that was inevitably going to happen in the process of democratization. Chun Doo-hwan's regime locked up beggars because they wanted to show off that they had a very good welfare system and didn't have any beggars on the streets. However, this case exposed the barbaric regime's nakedness, and the level of our society along with the judiciary's nakedness. It was a case that stimulated the interest of our society, especially in relation to what physical freedom is."

In closing, Kim expressed special thanks to then Ulsan District Chief Cho Jae-seok. "If he hadn't pushed me to investigate, I wouldn't have been able to do it," he said.

"With that support, we've released 3,000 people. Our biggest accomplishment is not getting convictions. If you're convicted, what do you do? You do two and a half years and then you get out.... Our biggest accomplishment was freeing 3,000 people."

Practices:

Source:오마이뉴스